In recognition of National Victims and Survivors of Crime Week, we are proud to host, in partnership with Justice Canada, a week-long community art exhibit and awareness series centred on the impact of crime on women and girls in the BC Interior. This project gathered narratives from women who are survivors and family members whose daughters were victims of crime within our communities. Weaving the community support around the narratives, providing space when women could not hold space for themselves. -

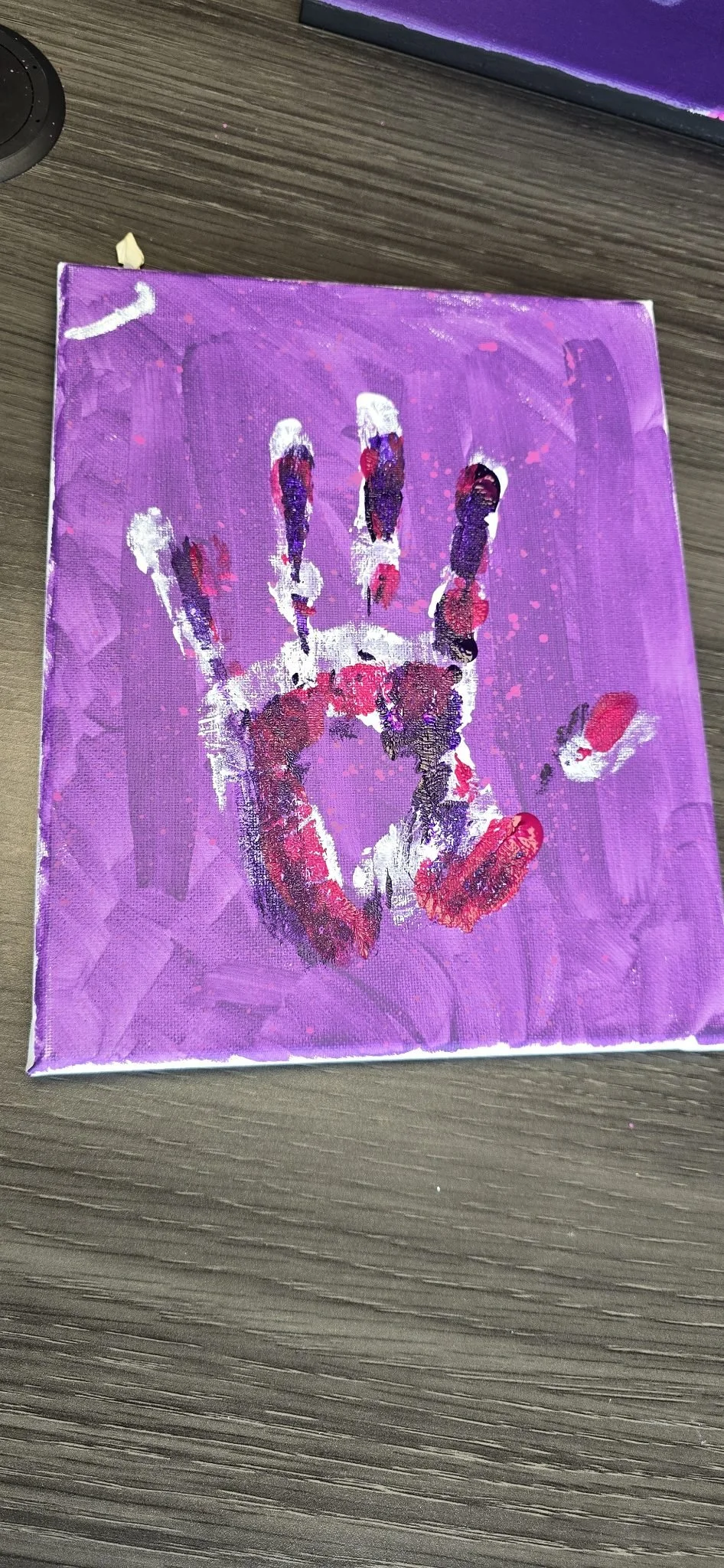

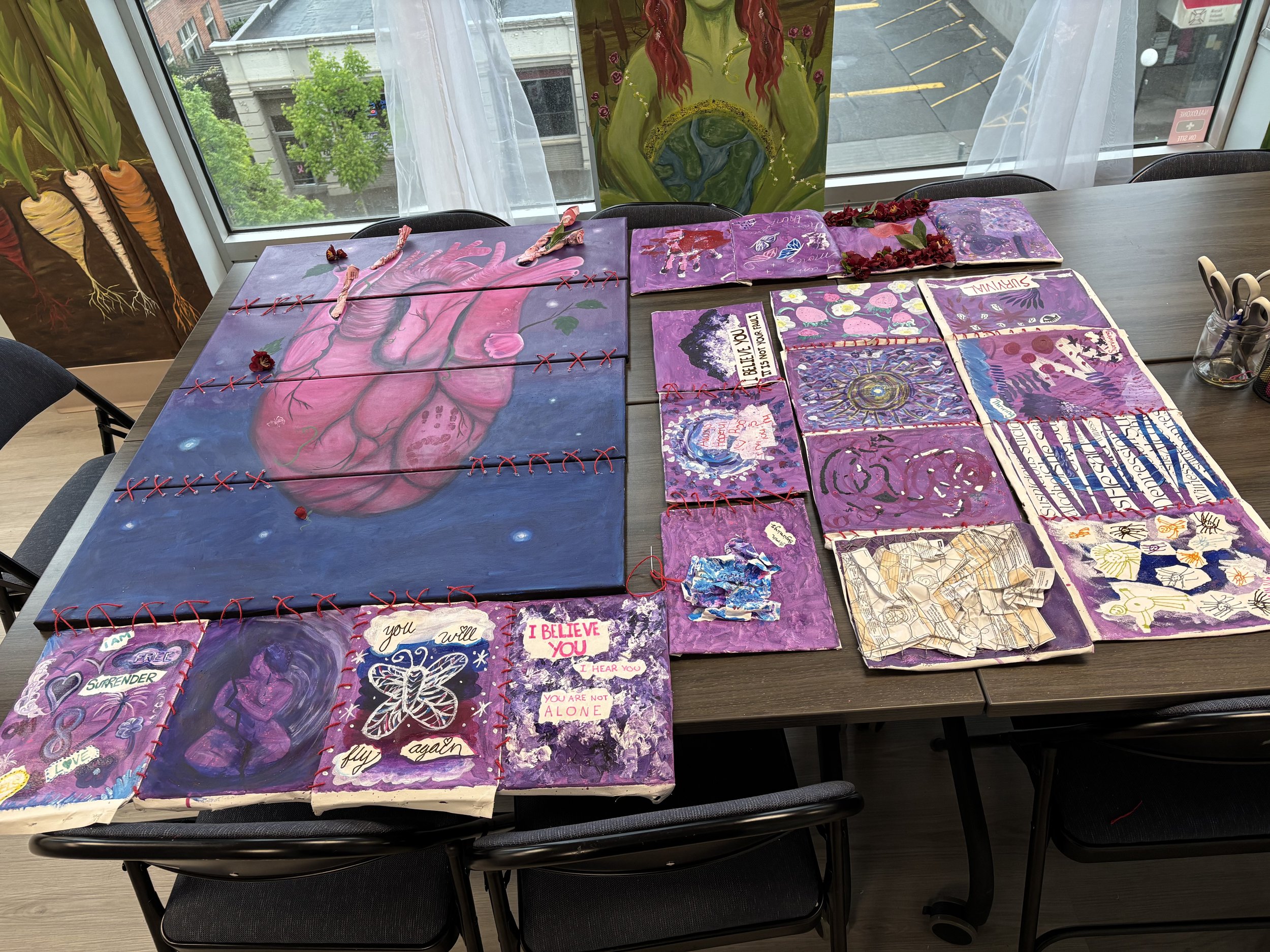

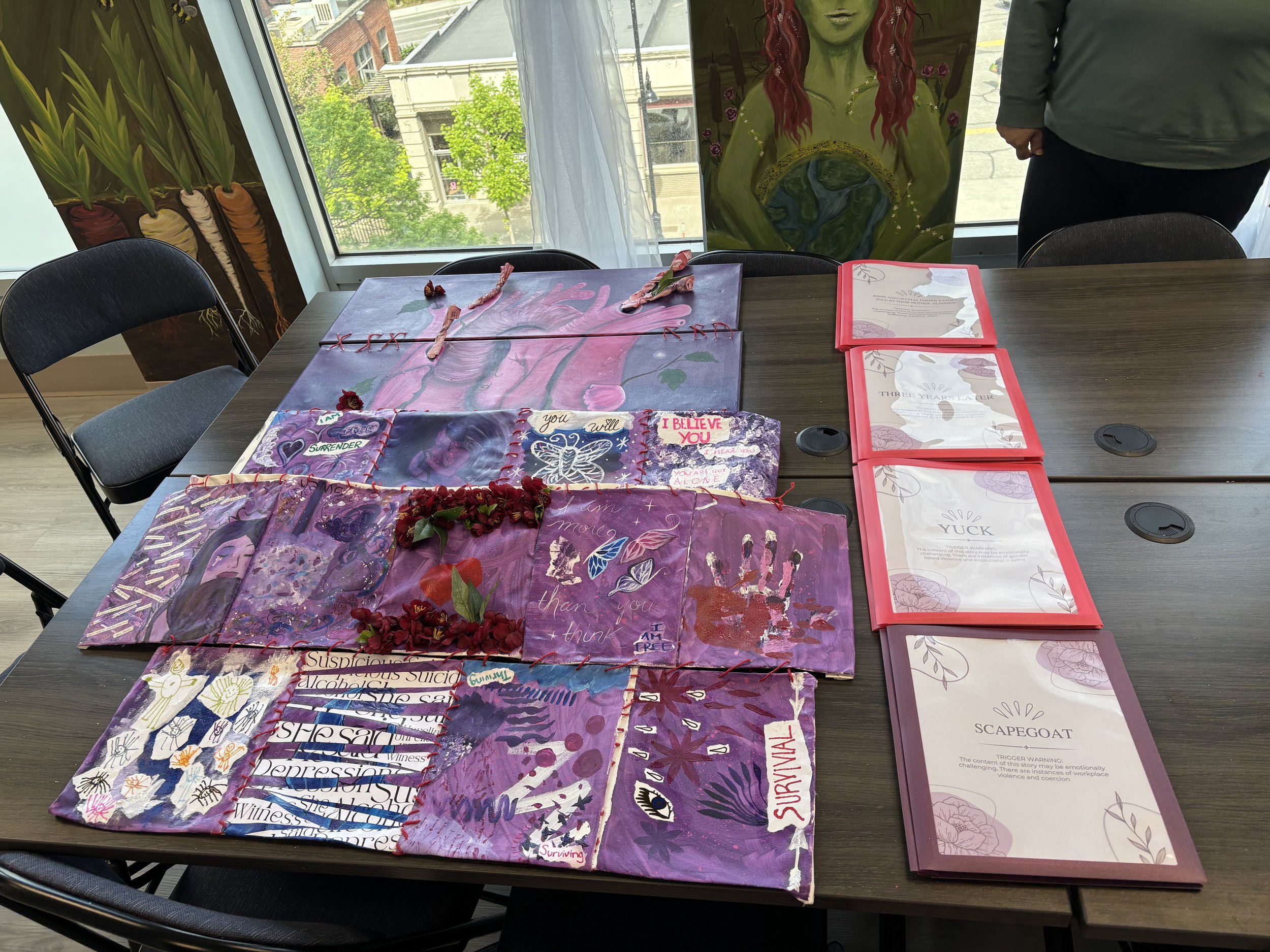

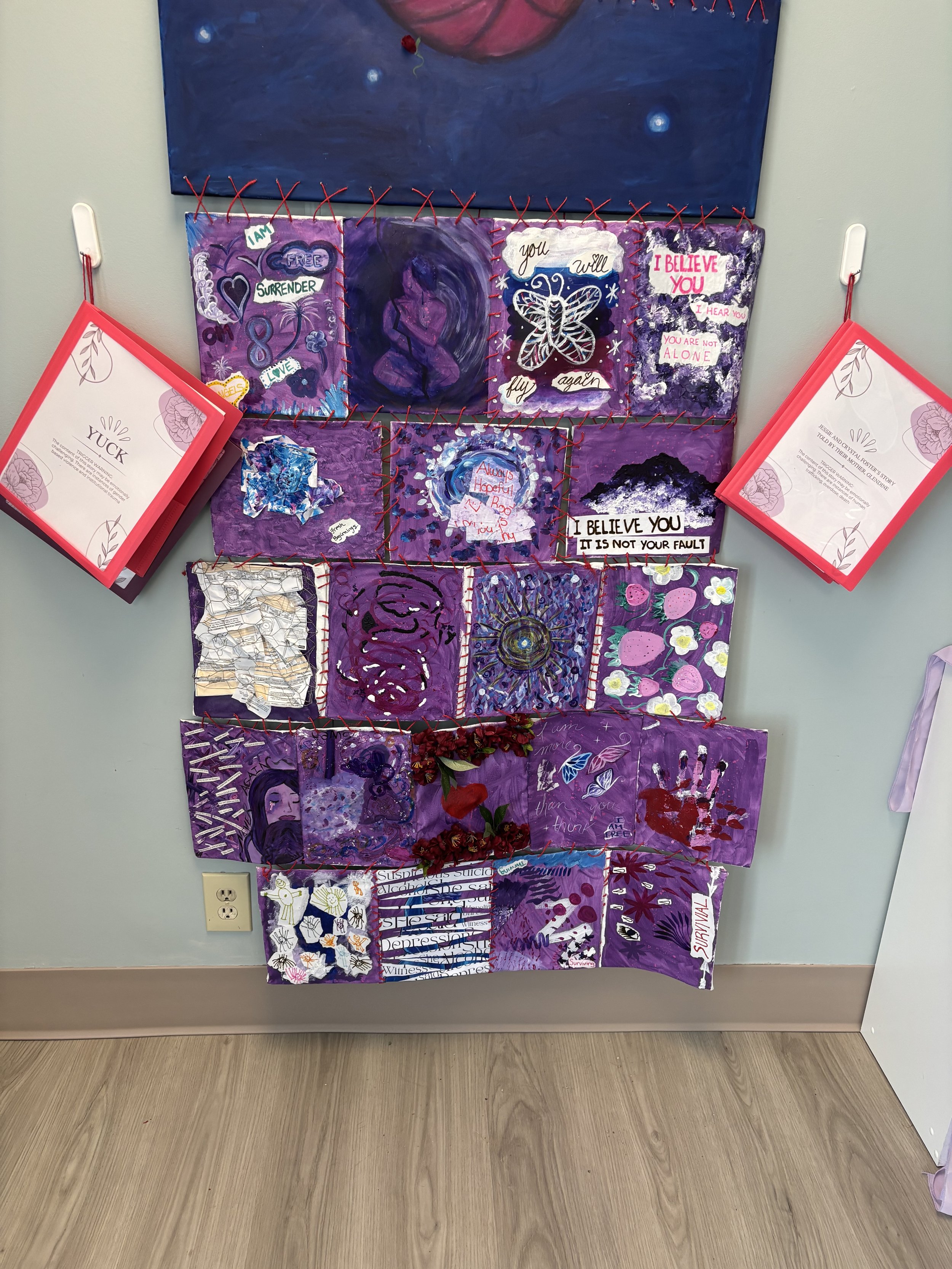

At the heart of the event is a community-designed and developed art installation, created by and for victims and survivors of crime. This powerful piece will serve as a symbolic and emotional centrepiece of the week, showcasing lived experiences, healing journeys, and a collective call for change.

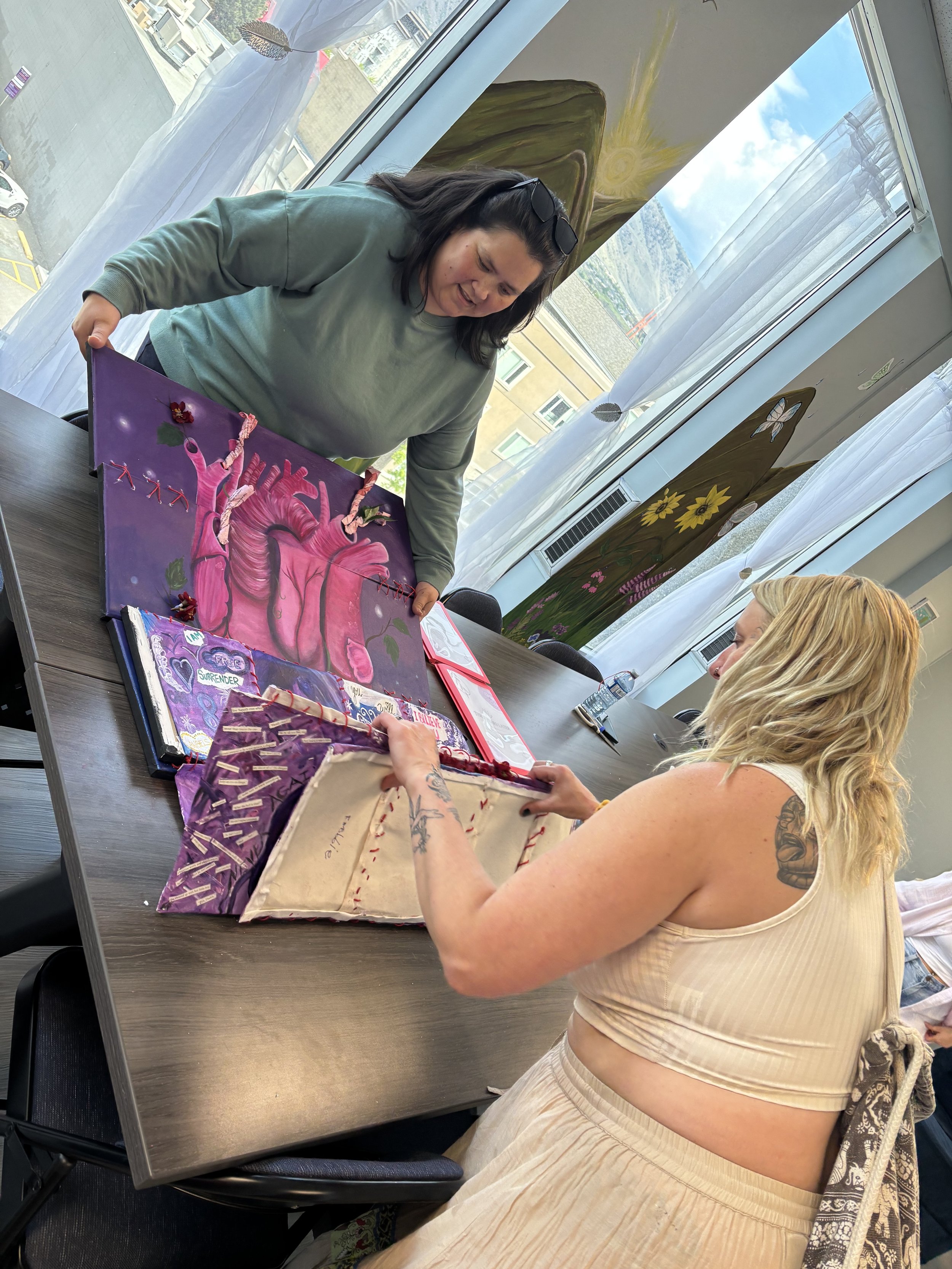

To gather stories and foster creative participation, we hosted two Healing Art Circles—safe, supportive spaces where individuals were able to engage in artistic expression, reflection, and community care. These circles informed the final installation and deepened the emotional resonance of the exhibit.

The completed piece is on tour, travelling to various venues across the City of Kamloops to gain visibility and attention, telling the story of change that needs to happen within the community. Our project leads will be speaking to the piece at Artisan Bazaar, The North Shore Library and at a private viewing and paint circle on the last day - May 17, for all who supported and took part in the project.

The piece will continue to be displayed at Artisan Bazaar for 3 weeks, and will then be mounted at the Kamloops Women’s Centre.

Application has been made to galleries for 2026 to have this symbolic piece shared further, publicly. -

The Victims of Crime Project matters because it gives voice to the silenced, visibility to the invisible, and power to those who have endured harm, many in silence. It is a platform to tell the truth, hold systems accountable, and begin or continue healing. Survivors are often retraumatized not only by the crime itself, but by the institutions that fail to support them afterward. This project seeks to change that narrative by centering lived experience, educating communities, and advocating for systemic change.

Here’s why it matters:

❗ Victims of Crime Face Deep and Lasting Impacts:

Many survivors experience PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use, and social isolation following victimization.

Women, Indigenous people, people with disabilities, and 2SLGBTQ+ individuals are disproportionately impacted and less likely to receive justice or adequate support.

-

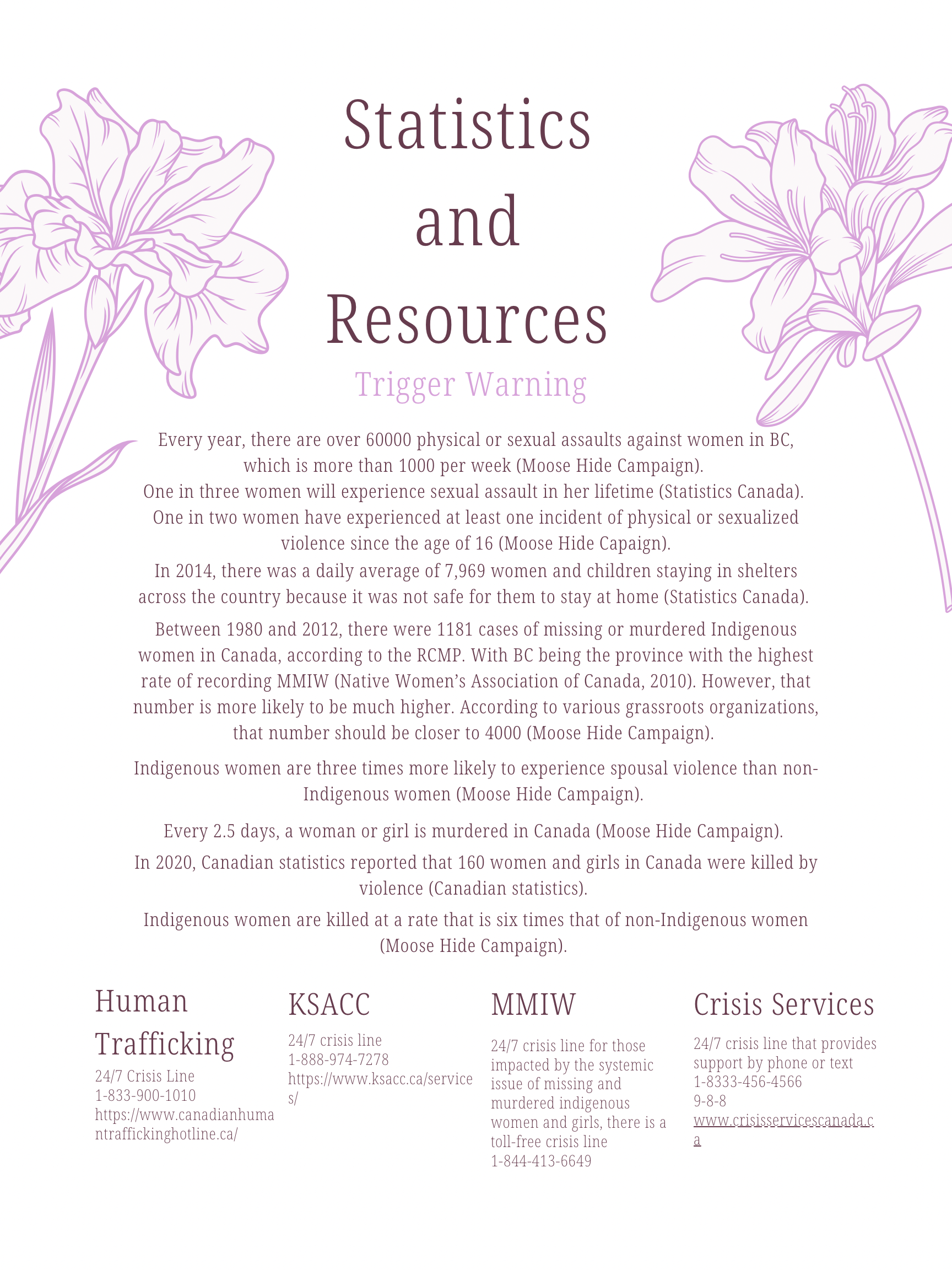

Over 6 million Canadians are affected by crime every year—yet less than one-third of crimes are reported to police (StatsCan, 2023).

70% of Canadian women will experience gender-based violence in their lifetime.

1 in 3 women globally has been subjected to physical or sexual violence (WHO).

In 2023 alone, over 160 women and girls in Canada were victims of femicide.

Indigenous women are 12 times more likely to be murdered or go missing than non-Indigenous women (National Inquiry, 2019).

1 in 4 women in Canada has experienced workplace sexual harassment, and nearly half report experiencing discrimination or bullying based on gender (Canadian Women’s Foundation, 2022).

-

It validates survivors’ stories.

It educates the public on the real human cost of violence and systemic failure.

It builds community, bringing people together to demand better policy, protection, and prevention.

It heals, by providing space to be heard, believed, and supported.

This project says: we see you, we believe you, and we’re fighting with you.

Because change begins when stories are told, and justice begins when we start to listen.

-

We approached the gathering of these stories with the care, dignity, and intentionality they deserved. For many, the act of sharing their experiences was not just a contribution to a project—it was an act of courage, of reclaiming their voice.

Some women submitted their stories independently, in their own words, when they felt ready. Others chose to share in person. For these intimate conversations, we created quiet, respectful spaces—often sitting over tea—where women could speak freely, without judgment or rush. These moments were tender and sacred. Our project coordinator recorded these stories with full, informed consent, and later transcribed their words with the utmost attention to tone, meaning, and emotional nuance.

Before anything was shared publicly, each story was brought back to the storyteller. This final step ensured that the narrative reflected their truth—no words twisted or taken out of context. It also allowed them the power to revise, withdraw, or approve their story in a way that felt right and safe for them.

This entire process was led through a trauma-informed lens. Every member of our team brings experience in mental health and understands the complexity of trauma, not only its impacts, but also its nonlinear pathways toward healing. We were mindful of emotional triggers, practiced active listening, and upheld consent at every stage of the process.

We did not just collect stories.

We held them.

We honoured them.

We protected them.And in doing so, we affirmed a foundational truth: that storytelling, when done ethically and with care, can be a profound tool for both individual and collective healing.

-

At the heart of this year’s Victims and Survivors of Crime Week, our project underscored one of the most essential forces in healing: collaboration. We brought together service providers and community members—those on the frontlines and behind the scenes—who have walked alongside individuals impacted by crime. These are the people who show up in moments of darkness, often for strangers, offering care, support, and solidarity when it is needed most.

This gathering was more than an event—it was a testament to what becomes possible when a community unites with a shared purpose. Whether responding to intimate partner violence, workplace harm, or systemic injustice, these collaborators have supported survivors in regaining their voices, dignity, and agency. In many cases, they have held space when survivors were unable to do so for themselves.

The purpose of this project was to spotlight the power of community collaboration in responding to violence, particularly the injustices women face every day across our neighbourhoods, cities, and systems. Healing does not happen in isolation. It takes networks of care, trust, and action to rebuild what has been broken. When a survivor cannot speak, the community must speak for her. When she cannot stand, we must stand with and for her. This is the power of collaboration: a collective, unwavering presence that says, “You are not alone.”

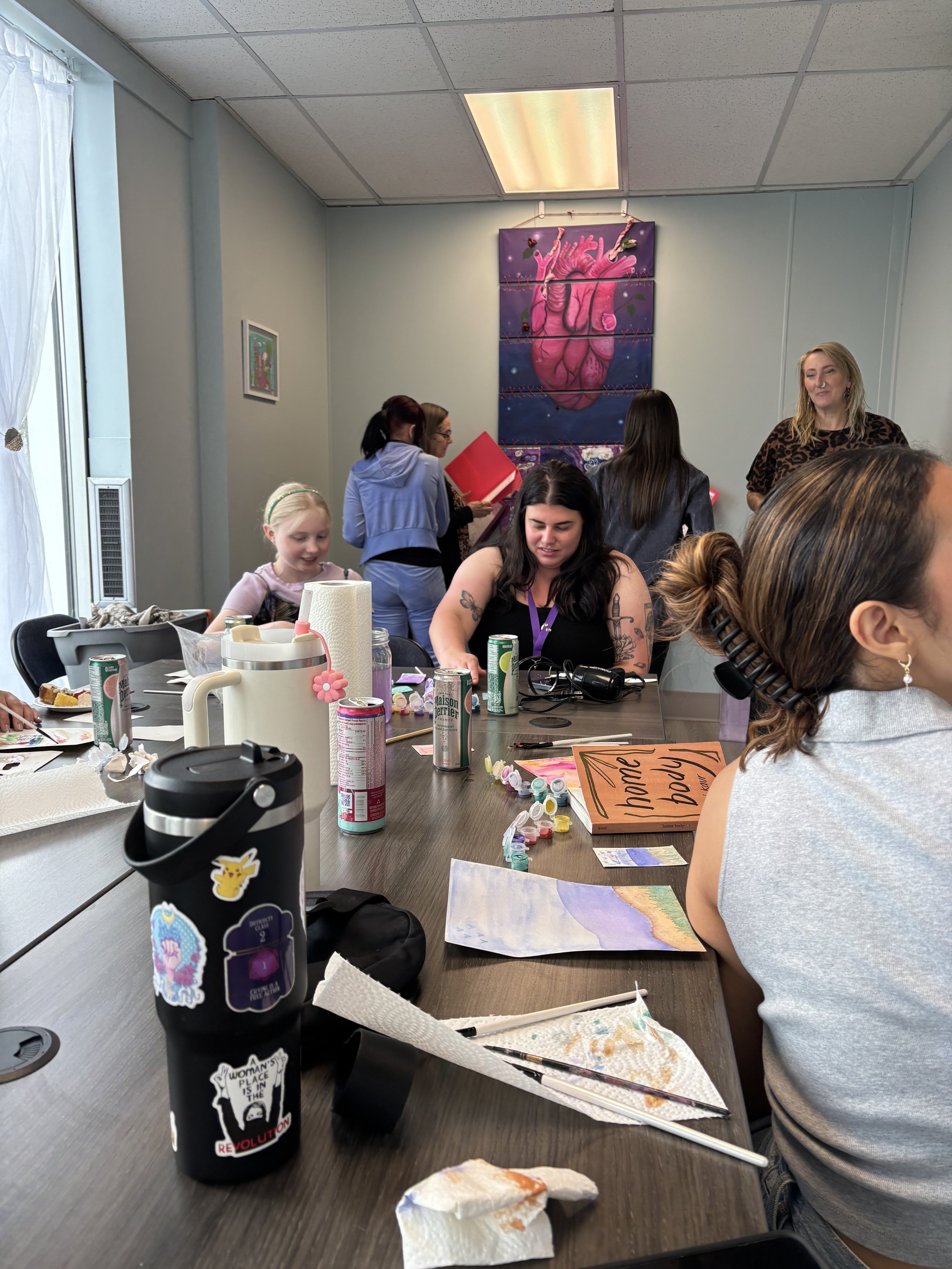

As part of this broader initiative, we invited service providers and community members into a series of healing art sessions—spaces intentionally created not just for reflection, but for release. These sessions offered more than just paint and canvas. They became sanctuaries for those who give of themselves daily—counsellors, advocates, outreach workers, peers, and neighbours—who have supported individuals impacted by some of life’s most unimaginable atrocities.

Whether helping someone they have known for years or a complete stranger, many carry the emotional weight of vicarious trauma. Through brush strokes and bold colours, participants were able to express their own emotions—grief, love, exhaustion, and hope. These moments became opportunities to tend to their own hearts while honouring those they support.

In sharing their artwork, they also shared their humanity, reminding us that healing is not one-directional. Helpers, too, need holding. The result was a powerful tapestry of care—visual expressions of solidarity, strength, and shared healing. In a sector where burnout is real and compassion runs deep, these sessions reinforced a simple truth: those who care for others must also be cared for.

Through storytelling, art, and intentional gathering, this project demonstrated that when we come together, when we witness, support, and uplift one another, healing becomes possible. Collaboration is not just a strategy. It is a lifeline.

-

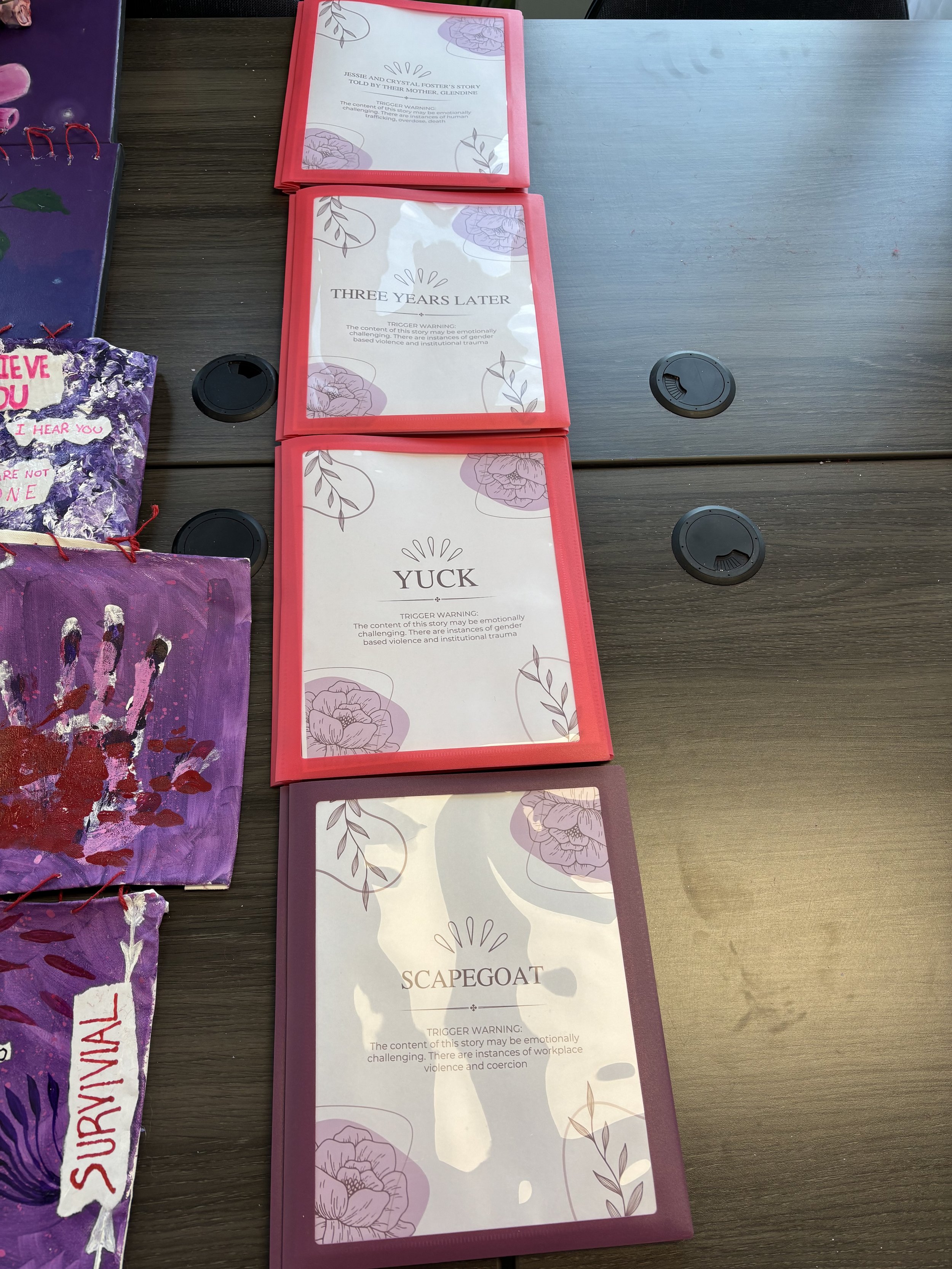

At the centre of this year’s Victims and Survivors of Crime Week project were four courageous narratives—survivor stories that formed the beating heart of our work. These were not just stories. They were raw, emotional, and deeply personal truths shared by women whose lives were forever changed by violence. Family members who lost loved ones to human trafficking. Women who survived intimate partner violence, workplace harm, and gender-based abuse. Their voices carried the weight of lived trauma, the resilience of survival, and the righteous anger that often comes with both.

These stories were not polished or packaged. They were shredded—torn into pieces to reflect the pain, the rupture, the unspoken grief that so often goes unseen. In this visual metaphor, we honoured their complexity: the hurt, the frustration, the resistance to being “over it,” and the power of simply sitting in it. Because the truth is, we can’t always get over what has happened to us. We can’t move past those who have gone missing, or the ones who were taken too soon. But we can feel. We can remember. And we can let that memory move us toward action.

This heartbeat—the pain, the rage, the healing, the remembering—is the emotion behind the project. It is what propels the work forward. It is what demands justice for women across this country who continue to face unrelenting violence.

But at the core of it all were those four stories. They became the pulse of the entire project. They reminded us why we gather. Why we speak. Why we continue to advocate.

Because when one woman cannot speak, we must speak for her. When one is silenced, we must raise our voices louder. And when the systems around us fail to respond, we must be the ones to demand change.

This heartbeat is not just symbolic—it is a call to action. A reminder that silence is complicity, and awareness is only the beginning. We must keep talking. Keep learning. Keep organizing. Keep advocating. Because until every woman is safe, none of us are.

We carry the heartbeat forward. For the ones who are healing. For the ones who are grieving. For the ones who are gone.

Let it be loud. Let it be felt. Let it never be silenced.

HER STORY

(Trigger Warning)

-

A True Story of Resilience After a Sexual Assault

When I was 16, I left my home in Germany to spend half a year as an exchange student in Canada. I was excited and nervous, of course—but ready to experience the world, meet new people, and grow up a little. I never expected that I'd come back home carrying something much heavier than souvenirs or school memories. What happened to me wasn’t just a sexual assault. It was a life pivoting experience. And the silence that followed was louder than anything I’d ever known.

No one saw it happen. There was no video, no DNA, no proof, just me, my story, and the fear that no one would ever believe it. For 48 hours, I convinced myself I would never speak about it. I believed I’d take it to my grave. But something—some gut feeling—told me I had to try. I told a teacher I trusted. A male teacher, oddly enough, someone you wouldn’t expect to be the person to catch you in freefall. But he did. He believed me. He took me to the police, arranged for a German translator, and helped me start what would become the longest, hardest journey of my life.

When I returned home to Germany, I didn’t think I’d ever hear back from the justice system in Canada. I thought maybe my report would just fade into a folder on a desk. But three years later—after finishing high school, after grappling with PTSD, isolation, nightmares, and suicidal thoughts, I got the email: they had set a court date.

was doing work and traveling in Canada again when it happened, almost like fate. I ended up sitting in a courtroom, staring across at the person who hurt me, reliving everything. And then, something I never expected happened: the court convicted him. I didn’t even know it was possible. My social worker said she had never seen a case like mine end in a conviction. Not once in her six years.

But it didn’t erase anything. It didn’t heal my nervous system, which still flares up at the sight of someone who looks like him. It didn’t bring back the teenage years I lost to panic attacks and trauma. It didn’t restore my trust in the friends who turned their backs on me. In that small-town high school of 200 students, everyone knew what happened. And somehow, I became the villain. The girl who ruined a boy’s life. The girl who was just seeking attention.

Their silence and judgment hurt worse than the attack itself. But what came after, the support I eventually received, changed me. The police, the courtroom staff, the victim services worker who made sure I never ran into him in the hallway, the social worker who sat beside me, and later, the long awaited therapy I was finally granted—48 hours of it, when I thought I’d be lucky to get four.

I will never be the person I was before. I still live with PTSD. I still flinch. I still feel the weight of those who didn’t believe me. But I also feel stronger. I know now that I can survive even the worst things. And I know that speaking up, while terrifying, was the right thing to do. Even if it feels impossible, even if it takes three years, there is a chance. There is a path. There is support.

I don’t know if I’ll ever tell that teacher just how much his belief in me mattered. But maybe this story will reach someone like him—someone who needs to know that one small sentence like, “I believe you,” can change a life.

-

Woman | Survivor of Sexual Assault

2021.

I missed my best friend so much. They live in the lower mainland and I live in Kamloops. I had finally left my toxic relationship, and the covid restrictions were starting to lift. What better time to finally visit them for the first time since 2019.

That was the night that changed me from the inside out.

I woke up, with my shoes and makeup on in my best friend’s bed. We lie horizontal. It was past noon, I needed to take my morning medication. Everything was a blur, and I was so confused.

Why so confused when I “blacked out” when I should be hungover.

We go to the park. We cover up bruises. We try to piece together the night.

“We were probably drugged,” they said. The world stopped for me. “And if I remember what they did to me, I can only imagine what happened to you.”

In that moment, I was so focused on their neck, the marks, the subtle memories from the last night, I realized who knew what happened.

Concerned for our well-being, we went to the hospital. Got the pee test, the “rape kit” as it is called, the whole 9. We had the most traumatic experience there, and yet left feeling worse.

A few days later, we learnt that all of this was on the establishment's video system. We were advised to go to the police.

We did.

We regret it.

We were promised justice and ensured that our case would help others. We were wrong.

I have since learnt, not from my memories, but footage from the night, that I was sexually assaulted by 4 if not more, men. All on camera. All allowed to stay in the establishment.

I cannot speak from what I don’t remember, but the police said they would be charging 3 out of 4 suspects.

Turns out 4 out of 4 walked away free.

I am human, and my story matters. I have the privilege to not only share my story, but shine a light on how many others who have not had the chance. I believe survivors of sexual violence and your voice matters, no matter what the situation is.

-

Woman Leader | Survivor of Workplace Violence & Coercive Control

There are things I have survived that I can only write about in fragments.

Scattered truths, like broken glass glinting in the sun.

My PTSD shows up when I am in rooms with leaders, collaborative spaces for system changes and when I hear names of people whom I used to work with in the harm reduction world. My PTSD shows up as sweats, shakes, elevated heart rates, and near-passing out.

Overcoming what had happened to me has not been easy; it would have been much easier to change careers and move on to something else. Where no one would care or know who I am.That is what they wanted. I got too close to the sun, and jealousy turned to aggressive workplace violence, a breach of confidentiality, unethical auditing of systems and ultimately constructive dismissal.

I only know my truth, I am sure there was so much more under the surface as to what really happened within my former organization.

The year was 2019, and I had been working in harm reduction and overdose response since the crisis was declared in AB. I accepted a provincial role with an organization in deep distress. The staff were traumatized. Many had active substance use or complex mental health needs. There were no formalized HR policies, no safety plans, and no accountability. The organization had not had a proper audit in years. They were running on fumes, and funders were circling.

I was hired to work with the Executive Director to build and stabilize the agency.

So I did. The role was okay despite the pressure because I had a healthy brain to lean on, and a healthy stable colleague to navigate challenges with.

Eventually, I was promoted to Executive Director. Where I would stand alone.

I wrote Human Resource and OHS policies from scratch, trained peer supervisors, hired support staff, implemented payroll systems, and rebuilt the crumbling bones of the organization. I answered crisis calls at all hours. Picked up coworkers from ERs. Navigated employees who were exploiting vulnerable women, consistent harassment issues at work, and eventually, human rights issues. I was drafting reports from hotel rooms. Showing up as much as I could to stabilize, until I could not.

There was screaming. Intimidation. Personal attacks during meetings. Rumours of violence and misconduct were swept under the rug. I was harassed, gaslit, slandered, and called names I will not repeat. There were no boundaries, no consequences, no safety nets - and if implemented I was the abuser.

I was physically threatened by staff. People used mental health as a weapon. The board refused to listen because it was “nothing about us, without us.” It was dysfunction dressed as “inclusion,” chaos framed as “equity.” I was expected to be the therapist, the fixer, the punching bag, the employer. I was not allowed to hire pillars of strength without having my career threatened. Despite never receiving a contract stating I was the Executive Director. To prove I was, I had to utilize the board meeting minutes from 2021, where the Board had voted me in as the next Executive Director, promoting me from Operations Manager.The truth is: my human rights were violated. Every. Single. Day.

Despite it all, I increased the annual budget from $50,000 to $3.2 million in the few years I was there. I professionalized the agency on the outside. Launched programs. Raised salaries. Provided Jobs to folks with work place barriers. Secured health benefits. Formalized leave. Brought in external HR. Built policies that should have protected us all.

But culture eats policy for breakfast.

I was always told I was “too corporate,” “too sensitive,” “too polished,” “too white.” My trauma-informed leadership was mocked. My boundaries were seen as control. My composure was interpreted as coldness. Implementation of policy and occupational health and safety was turned me into an abuser. The very structures I was praised for building became the weapons used to exile me.

People did not just burn out—they self-destructed. And I absorbed the flames.

The workplace violence escalated until I was drowning in vicarious trauma. I developed panic attacks, rage, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. I was misdiagnosed and overprescribed. I could not recognize myself anymore.

After resigning for the third time, I gave up my apartment, relocated cities, and gave everything I had to that agency. The board begged me to reconsider. I had already told them I was running on fumes.

A few months later, they threw me out.

They called it a “restructuring.” They told the community I was “too sick to lead.” Letters were being sent in to the board by team members I had not even met, speaking of how I had harassed and bullied them. All in a plot to have me fired because they did not believe I was a peer. I should not be there. The organization needed to be 100% peer-led.

They told the community that I had stolen, that I had robbed, that I am a criminal. All to cover up their own acts of corruption.

The woman who replaced me, informed the board and management that I was called the scapegoat.

But I was not what they called me — I was injured. I was violated. I was thrown into a burning building and blamed for the fire. My reputation was slandered, my name was smeared. I lost absolutely everything. From housing to professional connections. From family to friends.

While they worked to destroy me, they were lining their own pockets with lies and greed. I was the scapegoat for an organization that was begging for corruption.

Now I know, no amount of passion or funding can redeem a workplace that refuses to protect its people. Human rights must come first—before growth, before innovation, before ambition. If the foundation is rotted, the house will collapse.

I was forced to recruit from a landscape of scarcity—traumatized applicants with deep wounds and unchecked behaviours. And because there were no trauma-informed systems to hold the complexity, people got hurt. Repeatedly.

I realize now that I was not the problem.

I inherited a culture of dysfunction, enabled by a board unwilling to intervene, and that used coercive control, dangling my career like a carrot. If I did not do as they said, I would be fired. And a sector that confused martyrdom with leadership. I tried to build a path toward justice in a system that was never designed for it. Enabled by a board that lived in the gray, and only trusted the words that came out of deceptive mouths.

But I have carried those lessons forward.

Now, I get to lead the way I have always wanted to: with care, clarity, and structure. I build from the inside out. I centre human rights. I name violence when I see it, even if it is wrapped in progressive language. I never again confuse chaos with inclusion, or abuse with passion.

It is liberating to lead without fear. To build a culture that protects its people. To know I never have to shrink myself to fit someone else’s sickness.

There are things I have survived that I can only write about in fragments.

But I write them anyway.

Because silence protects the abuser. And I protect myself now.

-

Told by her mother, Glendine. Speaking about Human Trafficking.

It was 19 years ago, March 29, 2006, when my daughter Jessie went missing. She’d been living in Las Vegas since May 2005, and we didn’t know what was happening to her until after she was gone. Jessie was lured there by someone we thought was a friend, but it turned out he was a violent pimp. Unbeknownst to us, Jessie was being beaten and forced to work at an escort agency. She was hospitalized with a broken jaw, arrested, and charged with prostitution. It was only after we hired a private investigator that we uncovered the horrific, heartbreaking things that were happening to her, and we had no idea.

At the time, no one talked about human trafficking. I didn’t even know what it was. But after describing Jessie’s story to someone, they said, “That sounds like trafficking.” I started researching. The more I learned, the more I realized that’s exactly what happened to Jessie. This changed how I told Jessie’s story, I didn’t just say she was missing; I told people, “My daughter was kidnapped. She’s a victim of human trafficking.” But it wasn’t easy getting people to understand. Most didn’t want to believe human trafficking happened in North America. The police were no better. When I first reported Jessie missing, I was told trafficking didn’t happen in North Las Vegas, it only happened on the Strip. That ignorance cost us precious time. Jessie was last seen on March 29. Police didn’t take a report until April 9. Eleven days. Eleven days to clean up or destroy evidence, erase her tracks, and disappear.

The police didn’t do much to help us. The rotation of officers on Jessie’s case over the years was disheartening. Most were ineffective, some even dismissive. I remember one cop laughed at a voicemail I left, pleading for help. That’s what families are up against. So I call myself the lead investigator on Jessie’s case. Jessie’s father and I were left to hire the private investigators, print posters, and fly across the country, trying to get someone to listen. I have had conversations with the man who trafficked her, Peter Todd. He told me she’d left everything behind except her hairdryer and makeup. That’s how I knew she hadn’t left on her own. Jessie would never leave without her makeup. It seems like a small thing, but to a mother, that’s the clue that told me everything. I had to hunt Peter down myself, threatening to tell the police what we’d uncovered. He gave me different stories. One where she went to the dentist, and one where she had left when he went to the store. When I asked if he hurt her, all he said was, “I have business.” From that experience, I learned that if you listen closely and let people like him talk long enough, they'll unravel in their lies and tell you everything you need to know. Peter Todd never admitted what he did, but without saying anything, he told me everything I needed to know.

About four years ago, a new detective named Adam took over her case. He was a rookie back in 2006 and remembered Jessie’s case from the beginning. He was the same age as Jessie and had just started working when Jessie disappeared at 21. He’d worked his way up the ranks and asked to be assigned her case. For the first time in years, I felt a flicker of hope. He believed she was a victim. He connected her case to several other cases with possible links to known murderers whose violence against women had made national headlines. As more cases gained media attention, I received a large number of phone calls from media outlets across North America. I saved every number. If we ever find Jessie, I’ll call every single one and tell them we found her.

Jessie is Indigenous, but she’s white-passing. She was beautiful, young and blonde. I had stunning photos of her, so when she went missing, I was not afraid to use them to draw more attention to her case. I had to because her beauty was what got her case attention. But it hurt deeply to know that the attention she got wasn’t just because she was missing it, it was because the media will always pay more attention to beautiful young women who look like her. I carry guilt for that. I carry guilt that other mothers whose daughters went missing, like Jessie but never got the same headlines.

Through the years, Jessie’s story has been on the national news, TV shows, talk shows, magazines, articles, podcasts and books. One of those books, Invisible Chains by Benjamin Perrin, includes an entire chapter about her. We met while he was in the process of writing his book. This was shortly after Jessie went missing as well. When I told him Jessie’s story, he explained to me how Jessie’s case was as classic as trafficking gets. That changed my whole perspective. I went from thinking Jessie’s story was one in a million, to realizing she was one of a million. I’ve got binders full of newspaper articles, posters, emails, so many that I eventually had to stop printing them. There wasn’t enough room. Nearly two decades later, I still get alerts when someone does a podcast or video about her. I often comment to let them know I’m Jessie’s mom. I thank them. I answer questions. I correct the misinformation. In the early years, people said terrible things about her. They made her out to be someone she wasn’t. I used to care so much about correcting the narrative. I still do, to a point. But more than anything, I want the truth to be known. Jessie was not the villain, she was the victim. She was my daughter, she was trafficked, and she deserves justice.

One of the few things that kept me going was the support from the community. People across North America helped us spread Jessie’s story. Some donated their time, and others just listened. When the justice system failed us, the people didn’t. We’ve had immense support over the years, and a lot has been donated to us. People have called us to give tips about Jessie's case. Some were false, but others were sincere. I’ve been sent pictures of women who might be Jessie. Some were alive, some weren’t. It was hard to identify them because how am I supposed to know what my daughter would look like if she’s been dead for a few weeks?

Talking about Jessie and sharing her story helped get me through the grief of Jessie going missing. If you’re behind me in line at the store and have nowhere to be, you’re going to hear Jessie’s story. In the beginning, I carried her posters in my purse. One time at the airport, I met a young woman heading to Calgary. She said she was running away but didn’t know what she’d do when she arrived. I told her about traffickers, about how they prey on women who look lost. I told her about Jessie and showed her Jessie's poster. After that, she cancelled her flight and didn’t get trafficked. Jessie saved her.

Jessie has helped save a lot of people. Her being missing inspired be an advocate for survivors and their families. I helped form an organization called M.A.T.H., Mothers Against Trafficking Humans, with another mom whose daughter was rescued just before being trafficked overseas. We wanted to turn our pain into action and advocacy. She has since passed away, and now it’s just me running the organization. But I carry it forward, for her, for Jessie, for all of the other girls. In both Canada and Nevada, I’ve helped shape laws to protect families like mine. In Canada, Jessie’s story helped push for laws that criminalized prostitution and pimping while focusing less on punishing the women. In Nevada, I testified to help erase the statute of limitations for survivors and families to sue their perpetrators civilly. Before that, we had only two years to act, which is an unrealistic timeline for anyone living through trauma or working through the justice system. Now there is no statute of limitations. This gives people like us more time and more hope.

After Jessie went missing, I began connecting with other families who lost their children the way I lost Jessie. Some stories were worse than others. Some found their daughters. Some didn’t. But they helped explain to me the importance of getting answers. Some believe they are ready for answers, or they think they know what happened. But other mothers have told me that truthfully, nobody is ever really ready for these answers. I’m ready for answers, even if they hurt. We all are. My grandchildren deserve answers. A whole generation is growing up with questions. They deserve peace.

I’ve come a long way. I’ve learned to enjoy life again. Not just for me, but for Jessie’s siblings, for her nieces and nephews, for every woman who never got her story told. I’m still here, I’m still talking, and Jessie’s story is still changing lives

Crystal’s Story – Told by Her Mother, Glendine

Crystal was my oldest child. She was the first person in the world to change my life. Her father and I never wanted kids, but when I had Crystal, she changed everything. She was born in 1982, but when she was 38, she passed away. She was the big sister of four. They all went to Lloyd George Elementary School. Crystal and Jesse were very close in age. When Jesse went into kindergarten, Crystal was in grade one. So they had the same friends growing up. The two girls were so close that you couldn't say one's name without the other. When Jessie was in grade 11, she wanted to move to Calgary to live with her dad for a year before she graduated. When Crystal finished school, Calgary became home for her, too. The girls even got an apartment together.

Crystal was 22 when Jessie went missing, and I know she never fully recovered from her little sister Jessie's going missing. Crystal felt the burden of losing her younger sister and was tortured by the fact that she did not know what was happening to her. She felt responsible somehow, like she should have known, should have protected her. But the truth is, had Crystal known what Jessie was going through, it would’ve put her in danger too. She would have wanted to help Jessie leave her situation. Any form of intervention or help that Crystal could have given Jessie would have put Crystal in danger, and the men who were trafficking Jessie would have probably come after her, too.

Years after Jessie’s disappearance, Crystal moved back to Calgary to be closer to her father. When she moved back, she reconnected with her ex-boyfriend from years before. Someone I never trusted. He was a hardcore drug addict and a very well-known dealer in Calgary. He pulled Crystal into his world. Her boyfriend’s influence, paired with the grief of losing her sister, led her to a drug addiction.

Then, two years after Crystal returned to Calgary, her Father passed away. We assumed he passed away from natural causes. He had collapsed and passed away at home. But the autopsy revealed something none of us expected, which was fentanyl. He had no history of drug use, no reason for it to be in his system. That’s when the questions started. Prior to her father’s passing, he told Crystal how much she would inherit. He begged her not to tell anyone, but she told her boyfriend. Two weeks later, her father was dead. Shortly after her dad’s passing, Crystal passed away as well.

Her funeral was in October 2021. My family didn’t want me to, but I invited her boyfriend. I knew he wouldn’t show up because he knows that our family all believes he killed her. We have no proof, but we believe it is what happened. According to the autopsy report, Crystal died of a fentanyl overdose. But Crystal didn’t use fentanyl. She avoided opioids and had to stay clean for work. When I asked her boyfriend how she ended up with fentanyl in her system, he told me she ate it because it was in her food. If he wasn’t there, like he claimed, how did he know what she ate? And how did he know what killed her before the autopsy came back? The more he talked, the more I just let him speak. That’s what I’ve learned from years of dealing with people like him and Peter Todd, the man who trafficked Jessie. Let them talk because eventually they’ll tell you everything you need to know. Narcissists always do. He tried to get her money. Before we even knew he was involved, he had already stolen thousands of dollars. He tampered with estate paperwork without any legal right to do so. But I was notified. I connected with lawyers, and I’ve got help now. We’re working to ensure he doesn’t get away with this and to get justice for Crystal.

***I don't think people ever stop mourning, you just learn how to cope with grief. I don't know why people feel the need to fill the hole in your heart that grief leaves. I don't need to fill that hole. I could not even imagine it because this grief and missing Jessie has now become a part of my love for her. The last time I saw Jessie, she was 21 years old. In my heart, she stays at that age. Since Jessie's dad and Crystal have passed away, they never got an answer about Jessie. Her Dad always thought she had passed. I never got there. It puts my heart at ease thinking of the three of them together.

Raising Awareness Through The Week…

-

May 14 Tabling | 1130 - 230

Artisan Bazaar | 705 Victoria St.The Art Exhibit runs from May 13 - 16.

We started the week off at the Artisan Bazaar, showcasing the piece in their artisan gallery. Several people connected with our team to learn about the piece and the purpose behind raising awareness for Victims and Survivors of Crime Week.

-

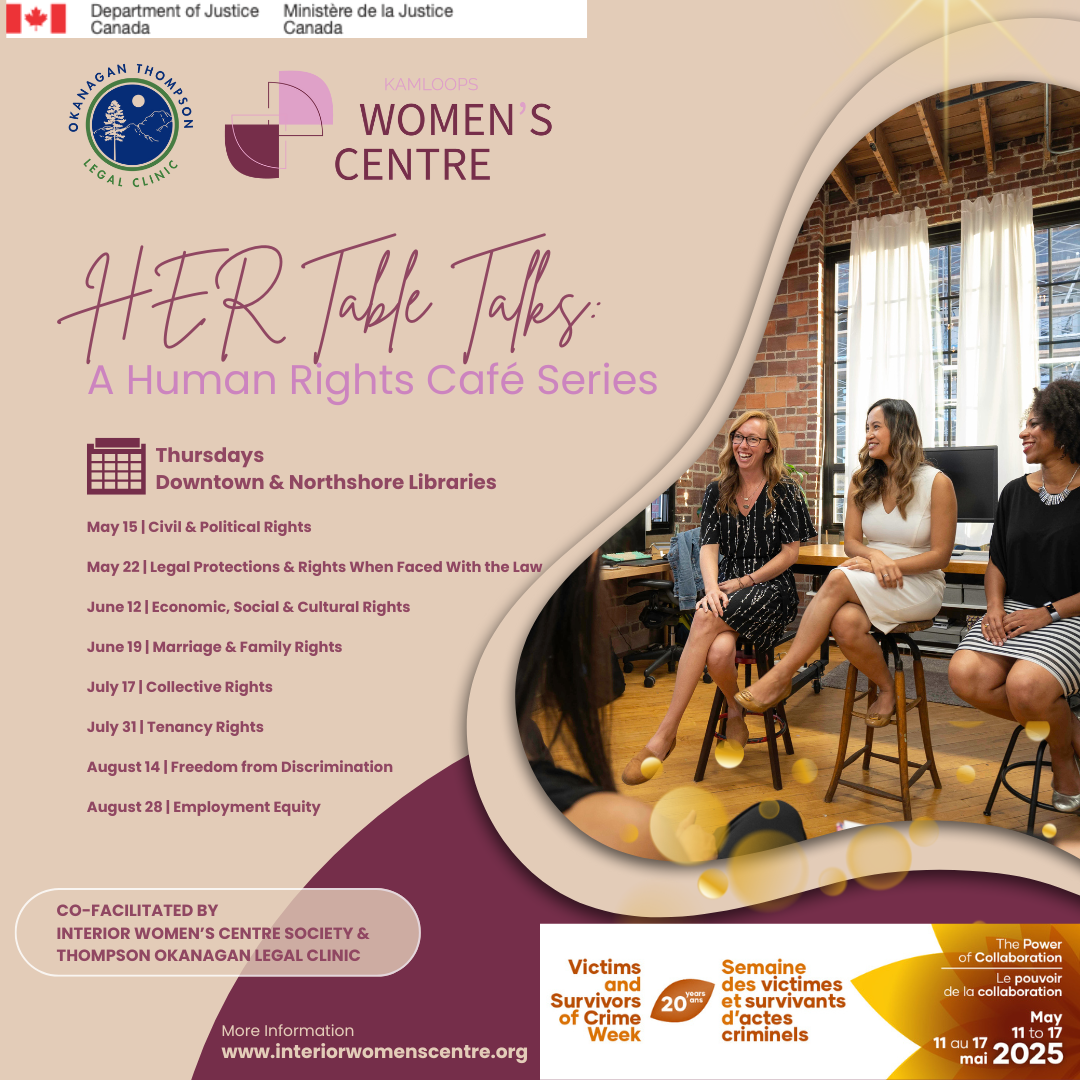

May 15 | 2pm - 330pm | NS Library

Midweek, we launched our Human Rights Café, focusing on civic liberties, justice, and policy reform, particularly as they relate to the human rights of women and girls impacted by violence and systemic barriers. We discussed how to advocate for change within our communities, and different ways that community members can get involved and be a voice within their communities.

Here’s why it matters:

❗ Victims of Crime Face Deep and Lasting Impacts:

Many survivors experience PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use, and social isolation following victimization.

Women, Indigenous people, people with disabilities, and 2SLGBTQ+ individuals are disproportionately impacted and less likely to receive justice or adequate support.

-

Artisan Bazaar | 1130am - 230pm

Our team members were at the Artisan Bazaar for the open house viewing on Friday, wrapping up the week. Several people came out to see the piece and to discuss the issues of crime within our community. Service providers from the community had also stopped by to learn more about the work and take part in the discussion.

-

May 17 | 11am - 1pm | Kamloops Women’s Centre

To conclude the week, our team hosted a private wrap-up celebration for all project participants. This gathering featured reflections from the lead artist and team, a message from the project lead on raising awareness for injustices toward women, and the opportunity to view the completed art piece together. Ending the week with a water colour art circle, reflecting on how we see ourselves, and how we hope to grow into the future. Each participant received a memoir from the project, as a gesture of appreciation for their courage and collaboration. -

To end the the project, the Interior Women’s Centre Society worked with with the Western Canada Women’s Foundation to launch the SHE Speaks: Unmuted Podcast, which will be utilized as a platform to discuss the Pink Elephant Topics that impact women in all aspects of life. This space will invite community members, field experts and other diverse voices to start the dialogue around womens rights, equities and ongoing issues within our communities, while also celebrating being women and all of the achievements that we are a part of within our communities.

Stay tuned for the first episode - set to launch in early June!

SHE Speaks: Unmuted

Episode 1: Meet the Founders of the Interior Women’s Centre Society